Back in 2005, I discovered Irish author John Banville and his Booker Prize-winning novel, The Sea. His protagonist Max Morden is recently widowed and dealing with earlier losses in his life. Personally, I found Morden to be insufferably self-absorbed—which is a cruel thought, really—the man is in mourning! And yet that is the drum-beat of the novel as I remember it. My eventual connection to the work came from the character’s final catharsis–his awareness of others, of emotions, of pain.

I was also taken with the complexity of Banville’s writing, and although at times it seemed a bit much—big words when smaller ones would have done just fine—I decided it was part of Morden’s characterization—the stuffy formality of his ego. After all, many of the critics of the era considered Banville to be “a master stylist of English” . . . “perfectly crafted, beautiful, and dazzling.” Some wrote that he was “known for his dark humour and sharp wit. . . the heir to Proust via Nabokov.” I thought at the time that he was a great antidote for some of the shallow novels that were being published.

In the years that followed, I read more of his works, and he seemed to be stuck with that same protagonist, a Max Morden look-alike: a self-absorbed man so involved in himself he could not even imagine the pain or struggles of others. I suspected, as well, that the recurring protagonist was patterned after Banville himself, so I put his work aside for decades. . . until more recently.

In 2025, I decided to read his new print – Venetian Vespers – only to find Banville has again stuck his reader inside of the mind of a pompous man, the self-absorbed hack writer, Evelyn Dolman. To make things worse, the story is set in the formality of the 1890s and written like a melodrama. Despite my prior criticisms of Banville, I expected so much more from a man that the literary press continues to identify as a potential candidate for the Nobel Prize.

And then again, there’s those big words. He has continued to over-write, using $5 words when a penny-a-pound would do. In the pre-read alone, you’ll find poignard, rood, emetic, tyro, eschew, puce, maw, churl, caracole, turbid, and foetor.

In reviewing “Banville” history, I came across a 2005 New York Times review of The Sea. That critic bemoaned the fact that there had been three stunning novels that year worthy of the Booker: On Beauty by Zadie Smith, Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro, and Saturday by Ian McEwan.

Instead, the Booker folks had selected The Sea, and the critic wrote paragraphs identifying what he found to be weak or objectionable in Banville’s work, including his persistent use of . . . you guessed it . . . grandiose words like leporine, strangury, perpetuance, finical, flocculent, anthropic, avrilaceous, anaglypta and assegais.

Apparently, Banville is out of favor with others—not just me.

JONNIE MARTIN

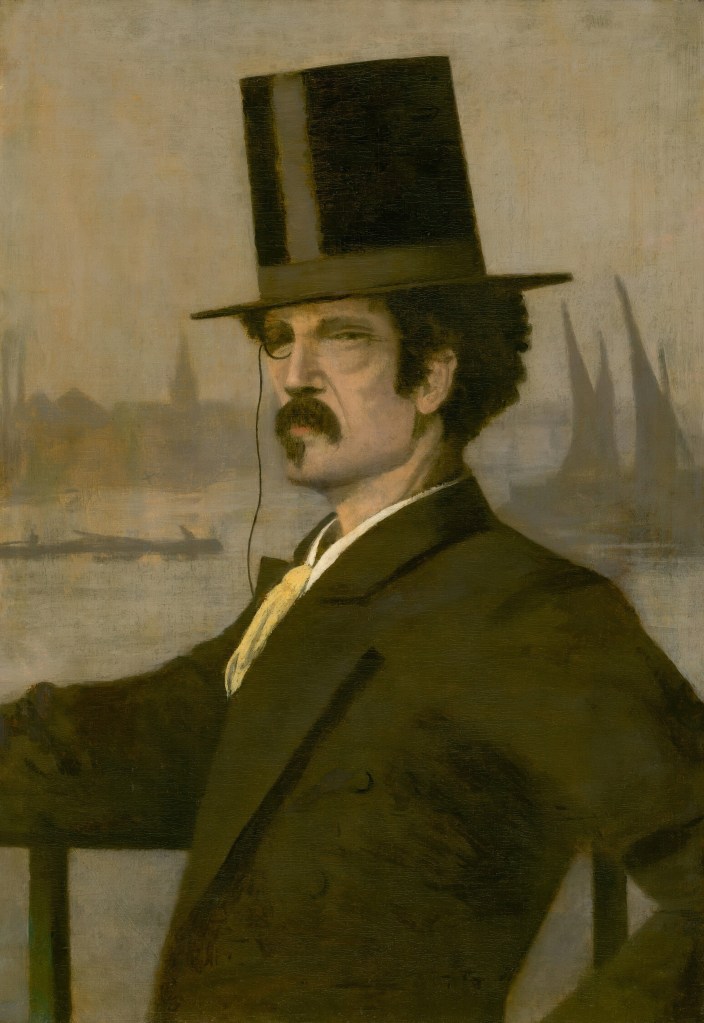

[Image: Art Institute of Chicago]

Leave a comment